Audio above. Check out the other posts on doireann.ie here

The poor trees. Getting it from all sides this past month. Frustration that needed a home I suppose, and understandably so when houses were a fortnight out. When I lamented a chainsaw’s massacre of trees around a house I often pass, the answer was ‘good, and a few more with them’. I said nothing; I knew my audience and my audience knows plenty about the damage falling trees do.

Safety trumps all, I know that. Some trees need to come down, I know that too. And I know that more will fall and be felled with the spread of ash dieback. But to me, a fallen tree is like an old vase smashed on a museum floor. A childhood playing among them and an schooling by the sea on nature’s sovereignty has left me with an idea of trees as village elders; as monuments to resilience, longevity, cycles, centuries and seasons passed, and all that was too ordinary to write down.

Back in 2020 I saw the world’s largest trees – the great sequoia – in California, the only place on earth where they grow in natural groves. We only stopped at that national park because we’d a few hours to kill before the car was due back in San Francisco, but of that entire week it is that afternoon that stands out most. Stand in a forest of trees that are about 30 feet (9 meters) in diameter and more than 250 feet (76 m) tall, some of them up to two and three thousand years old, and all you think you know or have a handle on flitters away in the wind. Much as the sea does, great sequoias remind us of our own insignificance in this ecosystem – and that is as freeing as it is humbling.

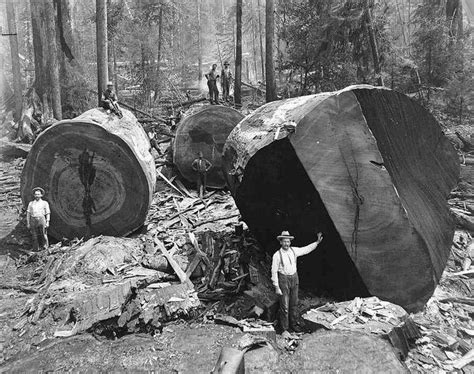

But existentialism aside – or perhaps not – what is more impressive about those great sequoias is their survival and resilience. Today they’re threatened by wildfires and extremities of climate. In the nineteenth century they were nearly felled to extinction as settlers and pioneers of that period tried to assert dominance over the daunting frontier landscape before them. Nature herself showed the folly of this, for the trees were of such weight that they would shatter upon impact.

But the notion of forgotten, faceless, nameless men trying to better that which had lived two thousand years before them and might live a thousand more beyond them really stuck with me.

That such literal giants were almost wiped out by the endeavour stays with me still.

I was walking through a forest recently, giving it loads to a friend on trees when she laughed and said, ‘Jesus, you’re big into trees aren’t you?’ I’m not really; I barely know one species from another, my respect for them is instinctive, not deliberate. A childhood of playing among them meant that I never saw the trees at home as lifeless, or as mere objects. (Enid Blyton and her Faraway Tree series might have a bit to answer for as well). The oak planted when one of us was born served as several imagined houses, offices, boats and hideaways. The bushes across the road were a hideout we all knocked seasons out of. The horse-chestnut trees beside the old house were stage, podium and lighthouse. In spring and summer when the ash trees were lush and heavy hiding the old house, I’d imagine I was Heidi in the Swiss Alps. Even now, when I see them bare and naked in winter, the thick bark splitting into branches that span and reach outward in glorious recipience, I am reminded of Olympic medallists with arms outstretched or Big Jim Larkin on O’Connell Street.

Those outstretched ash trees along the road in front of the old house are the most impressive. Seeing them through the steam of morning tea, I imagine them as a periphery of sorts; columns around a demesne of family history, scattered here and there in general proximity to boundaries that are and once were. I know really that such ash trees are rough and imperfect and unwieldy and gangly, with decay holes and twigs that point crookedly like gnarled witch’s fingers, but they’re also tall and mighty, commanding of respect; stately, grandfatherly. Aging without grace, as well they should be; of my family alone, they’re watching over the fifth or sixth generation at least.

It was those very trees I could see from my bed the night of Storm Éowyn through a six-foot window that had no curtains. The volume of the wind’s lash and the eeriness of its howl was one thing, but I could see its force in the pummelling of those ash trees, in the swelling of strength and volume with each renewed attack. I knew I might never see those trees standing again, and so for hours I watched them sway and swing and rock and shake. Defiant, taunting the old enemy.

Not, it should be said, that ash trees are in the position they once were to be taunting winds, for now to the list of their Judases of wind, age and human hand can be added ash dieback, a fungal disease first detected in Ireland in 2012 that will likely cause the death of the majority of ash trees over the next two decades.

Knowing of that extra vulnerability, I thought of what it would mean for those trees to fall.

Destruction and damage, firstly – and my own proximity to them that night was not lost on me.

Failure maybe; yet further victims of man-made climate change.

And loss. Loss of history and living symbols of permanence, real permanence, not the permanence we think we achieve in erecting buildings that rarely survive a century. My family have been up that hill forever, or as far back as we’ve sources for. And in that time, boundaries moved, land changed hand, newer houses were built and tracks become tarred roads. Generations of families were born, they lived, they left, and those who met them, saw or knew them are dead now themselves. Decades passed into centuries, names changed and Ireland transformed. But those trees stood.

And stand.

The single living constant.

A few weeks ago, during Storm Dara, a tree came down in the grounds of my workplace. Its enormity astounded me, but it saddened me too to see something so great sínte marbh on the ground. The same the morning after Storm Éowyn. The ash trees I’d been watching survived, but another one came down in the pigs’ field, its split bark like a gaping wound. I wondered then, if the fate of all trees is to end in rot or fall isn’t there honour in being felled by the mightiest storm of them all?

And glory in standing to see another day.