It was in the year of ‘95, in the middle of July

All Munster suffered sunstroke, and the grass was all burnt dry.

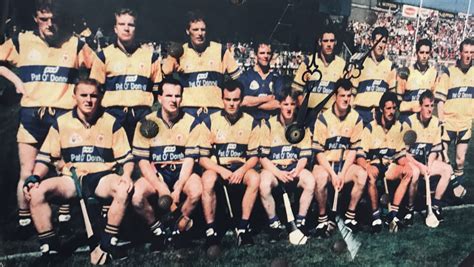

But the drought was at last ended by fifteen warriors brave and bold

When the green and white were brought to ground

By the Banner’s blue and gold.

The Banner Roar, by Ciarán MacDermott.

Pure poetry, wha’. I heard it for the first time in nearly thirty years when I woke up to it on Sunday Miscellany yesterday morning. I still know all the words. It was a song on a commemorative CD that came out in the summer of ’95 when the Clare senior hurlers reached their first All-Ireland in eighty-one years. I remember it like it was yesterday.

I remember it because what I knew about possibility as child, I learned that summer. Or to be specific, on the 3rd of September 1995, the day I found out that achievement was not the preserve of Everywhere Else, that mad and exceptional things could be done and could happen right here in the west of Ireland.

That gods could smile on us too.

I had a perfectly happy childhood in Roscommon in the nineties; going to matches, bouncing around the place, talking to trees, fighting with my siblings, and rinsing every adult I knew for sweets and jelly. But the world wasn’t at our literal fingertips like it is now; it came to us only via newspapers and two TV stations, and what was on them only more maiming and killing in Northern Ireland, young people emigrating and factories shutting. This is no Angela’s Ashes story, but I knew nothing of possibility because nothing ever happened and what did happen didn’t happen around here.

Football and hurling seemed to confirm that. Clare won a Munster football title in 1992 but didn’t go much further. Leitrim won a Connacht title and that was lovely, but they’d go no further and nor would Roscommon, should they even get that far. What I remember of Roscommon football at the time was an annual outing to Tuam or Castlebar, and how long the road home was. The solace stops at Supermacs only came later.

And that was fine, it didn’t bother me, sure I didn’t know any better. Cromwell had done a real number on the place, and it was just a fact that winning wasn’t for us, taoisigh wouldn’t come from the west, and the closest greatness would come was some emigrants’ offspring doing well elsewhere.

And then came Clare in ’95.

Dad is from Clare, so we knew a bit about the lonely roads out of Limerick and Thurles. The one flag did us for Roscommon and Clare, for all the use it’d get. Roscommon won Connacht in 1991, but went down against Mayo in ’92 and ’93. There was disappointment when Clare crashed out of Munster in ’93 and ’94, but not necessarily surprise. So when the sun blazed across Ireland in the summer of ’95 and Clare won Munster, it was lovely but I didn’t expect much to come from it. And then they beat Galway in a semi-final.

These were famously ordinary young men. And their leader was a teacher. Cousins of mine knew some of them. And what was greater than winning an All-Ireland? And if they did win, it’d mean silverware crossing the Shannon. And if it came once, it might come again, to a different county, maybe even to mine. And if that great thing happened, what other great things might happen?

On the 3 September 1995, Dad and the bigger ones went to Croke Park. I was glued to the television, a bag of nervous excitement, incredulous that my younger brother could play away with his tractors when this seismic event was on the tele. Every Offaly score was a dagger to my heart because Offaly didn’t need this, but I did; victory would not just be happy relatives and a championship shake-up, but hard and irrefutable evidence that mad and exceptional things could happen in the west of Ireland.

When the whistle blew and Anthony Daly stepped up on the podium, a rush of adrenaline ran through me and I ran out into the garden and whooped and hollered and waved that flag madly until exhausted, I flopped down on the grass, breathless beneath a glorious blue sky.

The world widened for me that day, and the following years confirmed this notion of possibility, of confidence. In 1997 I won a county title with the u-12’s girls’ team, and that year too Clare won again. It was looking good for 1998 too only for Offaly to put a halt to the gallop after three matches. But no matter, for that year Galway brought Sam Maguire west. In 2001 Roscommon won Connacht, the same year Galway beat Meath in the All-Ireland final. And the importance of these, their reach across county boundaries was captured by the woman who said that if the silverware didn’t go to Roscommon, as long as it came west of the Shannon, who minded who brought it?

I went to college in 2003, and I would struggle now to name any All-Ireland winners of that decade. And this week, when I wondered why that was, I copped that my dedication to Gaelic games – the validation and the confidence they inspired – lines up neatly with the rising economic tide. In the late nineties, the entire country was growing in confidence; emigrants were retuning, peace came to Northern Ireland, someone built a hotel in our town. But a little girl knew little of economics and national mood, and the progress others were measuring in GDP and exchequer figures, I was measuring in points, goals and trophies.

And wasn’t I dead right? Life was and is complex. For all that had been achieved in Northern Ireland, my first time in Croke Park came a week after the Omagh bomb, and what I remember most of that day is the haunted silence of the stadium as we stood to pay our respects to that atrocity’s victims. But I didn’t panic, because anything was possible.

September 3rd 1995 had taught me that.

I thought of that Sunday yesterday morning as I counted down the hours to the match. I think of it regularly, of wee me in the garden, and the epiphany of possibility, the realisation that geography didn’t limit us but made us. That we could do exceptional things. I’ll think of it again next Sunday and the Sundays after when Galway line out.

Knowing, as I’ve known this thirty years, that anything can happen.

Love it. Gaillimh Abú

LikeLike