The students I teach are on the last lap of the History curriculum; Irish history from plantations to the Rising. I try to emphasise to them that the dates aren’t important, nor are the names of monarchs or the titles of families. The main thing I want them to learn from their history is that Ireland today is one of the wealthiest countries in the world but it wasn’t always thus.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that in the week that has seen several American cities rocked by protests and riots after the killing of George Lloyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Having been dispossessed, having endured poverty and migration, and turned to arms to shake off the yoke of the oppressor, Irish people have an insight into aspects of standing up to injustice.

The US is full of good people who are generous, kind and proud of their country’s diversity. These people care little for the colour of their neighbour’s skin. Their front gardens have yard signs that say Hate Has No Home Here. But their goodwill is not being reinforced with institutional change.

But much of racism in the US is institutional – an unwritten or unspoken ‘the way we’ve always done things here’. If it wasn’t, a white police officer would not have killed George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for more than eight minutes.

Eight minutes is a long time.

Eight minutes suggests a perception of immunity to accountability, a feeling that this kind of action can be gotten away with. It’s part of an ingrained, systemic cycle of injustice that still exists in the US. The damage there was done long before a knee met a windpipe.

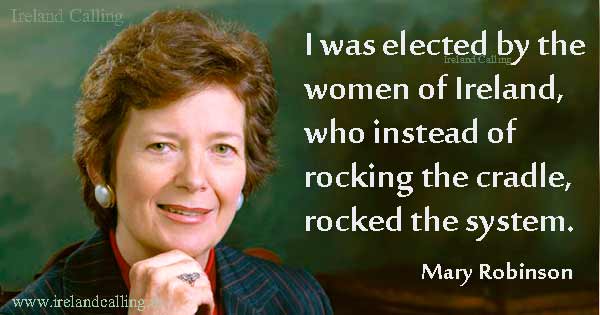

Racism in the US didn’t end with the election of a charismatic and youthful black man – and gifted orator – to the office of President of the United States in 2008. In Ireland, domestic violence and sexual assault did not end when a woman was elected president of Ireland in 1990. Elections of figures like Obama and Robinson are not the end-point of campaigns or movements; they’re just steps forward.

Going to Chicago in my thirties meant that I saw and noticed things that would’ve sailed right past me in my early twenties, namely how much easier life was for a person with white skin.

Near where I lived in Chicago, there was a Family Dollar store – like a €2 shop – with a sign saying that all backpacks would be checked. Not once, in all the times I went in there, was my backpack searched. The bags of others were regularly checked, people who weren’t white.

I was shopping one day in a discount store called Marshalls and I came out of the dressing room with six items instead of seven. I looked in the dressing room for the item, couldn’t find it. I explained to the attendant, and held out my bag for her to search. She just waved me on, said she was sure it was just a misunderstanding. That’s not how it works for other people.

As a woman, I have my own things to be looking out for when I walk down a street or go running. Being arrested, or shot at, isn’t one of them.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said that a riot is the language of the unheard. I think there are a lot of people in Northern Ireland that would see truth in Dr. King’s words, and people in South Africa, Burma, Venezuala, to name but a few.

Looting is wrong.

Burning cars is wrong.

Damaging buildings is wrong.

But if the looting, burning and damaging of buildings is the problem after this week’s events in Minnesota, then the actual point is being missed.

Riots happen when communities feel they’ve nowhere else to turn. They feel they’ve tried politics and communication. They feel they’ve told their stories, but were ignored by those with vested interests in the status quo. That the tinderbox ignites eventually is not wholly surprising.

We don’t know yet the breakdown of well-intended peaceful protestors and people looking for trouble. But dismissing an entire protest as being driven by people from out of town – travelling mobs, if you will – is to deny the validity of the entire protest.

Bloody Sunday, Derry 1972, is a case in point. Portray a valid and peaceful demonstration as hidden forces stirring up trouble, shoot protesters down, and pin the blame for those deaths on the innocent protesters.

I was in a bar in Chicago and a man hearing my accent told me about his recent trip to Northern Ireland. At the end of what had become a monologue, he stopped and asked me, dead serious like, “why don’t they just stop? They’re all Christians after all.”

Well, I tell you, I wasn’t ten minutes getting on the phone to Arlene and Michelle, told them to get a few of the crowd on a Zoom call because Chuck there from Chicago had just sorted the Northern Ireland conflict.

Everyone else’s problems look simple from the outside.

After all, the answer of the President of the United States to this week’s rioting in Washington DC, Minneapolis, Detroit, Atlanta, Portland and Louisville was “Get tough and fight (and arrest the bad ones). STRENGTH!”. Sure. That’ll sort everything alright.

I’m not saying the safety of citizens isn’t important, that rioting is actually fine. I am saying that riots in Minneapolis and St. Paul are not the real problem, but a symptom. The riots will have to be brought to a peaceful end, hopefully with no more loss of life. But quelling the riots isn’t the cure to the illness, the illness will continue to spread once everyone’s gone home or in custody.

Race in America is complex. Understanding that it is complex is a good start to grappling with racism. Many, if not most Americans are heartbroken not just at what happened to George Floyd, but to countless black men and women before him. They’re wishing for a better day for all Americans. Their goodwill and sympathy is not being backed up in the corridors of power.

There’s not an awful lot we can do from here, but we can at least summon our sixth class history to recognise and appreciate injustice – whether it’s Ireland in the nineteenth century or America in the twenty-first.